Escaping the False Twin Trap: A Therapeutic Approach to Strengthening Self-Esteem in Foreign Language Speaking

For most of my life, I believed you either had self-esteem, or you didn’t.

I thought this was especially true when it came to learning and speaking foreign languages. Some people just know they can do it and feel confident while doing so — while many others struggle with discomfort and anxiety.

When I was younger, I hated speaking English. I would speak slowly to avoid mistakes, yet I still made plenty. Every mistake I noticed felt like a sting. I expected more from myself. Producing accurate English was paramount; when I failed, I saw myself as incapable and stupid, and I feared others thought the same.

I didn’t realize it then, but that was low self-esteem working its dark magic.

Self-esteem in the context of foreign language learning

Most language learners agree that two situations are especially stressful and emotionally challenging: speaking in front of a group and speaking with native speakers. While this might seem obvious to anyone who’s struggled with a foreign language, it’s important to understand why these situations affect us so deeply.

I’ve been teaching German as a foreign language for 20 years and have met countless students with similar issues. For a long time, my advice was simple: improve your grammar and vocabulary, and push through your inner resistance.

But now, with a deeper understanding of self-esteem and how it works, I no longer give that advice. I’m convinced that both are battles of attrition that know no winner. On the contrary, following this path often traps learners in constant feelings of inadequacy and draining conflicts with their inner critics.

I’m pretty sure that’s not the kind of experience you want your language learning journey to be!

So, let’s take a closer look at what self-esteem really is and how it influences you.

One reason this topic is so tricky is the confusion around the concept itself. The term self-esteem actually combines several overlapping ideas. And in the reality of our daily experience these different concepts constantly overlap and involve each other. It’s probably fair to say that self-esteem means something similar — yet somehow totally different — to every learner.

Definitions of Self-esteem

On a macro level, self-esteem — fully realized — can be understood as the conviction that we are adequate for life and its demands. Applied to language learning, this means having confidence in our ability to learn the language on a structural level and use it effectively in real-life situations. Psychologists refer to this as self-efficacy: the belief in one’s ability to successfully perform and accomplish specific tasks or goals.

The need to feel competent and good about ourselves is a distinctly human trait. It’s no surprise that many influential authors view self-esteem as a basic psychological need, and the drive to enhance and protect it fuels without a doubt much of our mental activity and behavior.

However, this fact alone does not explain why so many people feel uncomfortable when speaking a foreign language. After all, engaging with that language in solitary activities – such as reading, doing homework, or even talking to ourselves – rarely throws us off emotionally, even when we perceive our skills to be rather poor.

Our discomfort when speaking must therefore stem from something more like stage fright. Language is a social tool, and humans are profoundly social beings. That’s why most of us find it difficult to separate what we think about ourselves from what we believe others think about us. Put simply: we tend to feel good about ourselves when we believe others feel good about us.

Sociometer Theory: self-esteem as a psychological gauge of social acceptance

This insight leads us to an illuminating theory about the evolutionary purpose of self-esteem – namely, why humans may have developed such a complex psychological system in the first place. It seems plausible that, in order to survive and reproduce in nature, people not only needed to seek the company of others but also to ensure they were accepted by them. Social cohesion – and thus the functioning of any community – depends on everyone knowing and maintaining their place within the group.

Building on these ideas, the American psychologist Mark Leary developed the so-called sociometer theory. According to this model, self-esteem functions as a psychological gauge that monitors our level of social acceptance. At its core, the desire to be seen in a positive light reflects our fundamental need to belong and be valued by others. Thus, self-esteem is not an end in itself, but a reflection of our perceived relational value – that means how included or excluded we feel within a social group.

Behaviors aimed at enhancing or protecting self-esteem – such as approval seeking, perfectionism, overthinking etc. – are not primarily driven by a direct need to feel good about ourselves. Rather, they are adaptive strategies to avoid social rejection and help us find our place in a given social situation.

The difference between state and trait

At this point, it might be important to differentiate, without going into too much detail, between the two concepts state and trait. In psychology, the former is a temporary, situation-dependent condition or emotion, while the latter refers to a stable, enduring characteristic of a person.

In our context, this would mean that state self-esteem is tied to one’s assessment of their perceived relational value in the immediate situation; whereas trait self-esteem is a compilation of our history of experienced inclusion and exclusion.

Let’s assume this is true and set aside the genetic component of self-esteem. Then, it seems reasonable to say that improving our trait self-esteem in the context of learning foreign languages requires two key steps.

First, we need to ensure that we can influence future interactions in a way that allows us to perceive both the situation and our role in it as successful. If general high self-esteem is the cumulative result of successfully managed individual situations, we must learn how to avoid undermining ourselves in these communicative experiences going forward.

Second, since we can’t go back in time to change a lifetime of formative experiences, we need to address the psychological patterns those experiences have put in place. As we will see, these patterns—once triggered by a sudden drop in self-esteem—can become major obstacles to experiencing ourselves as competent and in control of both ourselves and our social life.

How do we experience states of high and low self-esteem?

Perhaps the phrase “sudden drop in self-esteem” caught your attention. Even though we’ve introduced the distinction between state and trait self-esteem, it may still be strange to think of self-esteem as something that can shift from one moment to the next. That’s simply not how it’s typically discussed. And while you're likely familiar with how you experience your own trait self-esteem over time, it's worth considering what temporal states of high and low self-esteem actually feel like in the moment.

To ease into the topic, let’s begin with the more pleasant experience: state high self-esteem.

Contrary to popular belief, a state of high self-esteem isn’t marked by an exhilarated mood or the feeling of having won the lottery of life. Exaggerated swagger and explosive “big D energy” – à la Leonardo DiCaprio in The Wolf of Wall Street – are more likely signs of compensatory behavior rooted in low self-esteem or an artificially inflated sense of self, a condition usually associated with narcissism.

True high self-esteem is much more subtle. Perhaps the best way to imagine it is as the complete absence of negative emotion, psychic activism and self-conscious thoughts.

Let’s imagine a relaxed and engaging conversation with a good friend. In this moment, all our basic psychological needs are fulfilled: we feel in control, connected, and valued. Our perceived relational value is high and stable. There is no social threat – we are at peace with both our surroundings and ourselves.

Neurologically, this corresponds to a state of absolute consistency: our brains function without internal conflicts or irritations. We are in unconditional approach mode and a state of full congruence because our real-life experiences align perfectly with our activated motivational goals. As a result, we feel inner harmony, mental clarity, and a general sense of well-being. Everything feels just right.

As you can probably imagine by now, a state of low self-esteem is quite the opposite. Once we perceive – whatever the reason may be – that our relational value in the eyes of others is declining a progressively alarmist psychological response sets in. Neural inconsistency increases because our activated motivational goals no longer align with our lived experience. We shift from an approach mode to an avoidance mode.

We are acutely afraid of social rejection, yet we experience it as non-specific stress or anxiety. On a subconscious level, the brain concludes that the organism needs protection. As a result, and without our conscious mind ever having a say, it activates certain defensive patterns, that in the past have proven effective in alleviating neural tension and reducing inconsistency.

It’s important to remember that the striving for consistency is the fundamental driving force behind all psychological activity. Consequently, those defensive patterns follow an escalatory logic. They begin with simple strategies and gradually become more drastic, until a tolerable level of neural consistency is restored.

If you happen to be one of the many people who say, “Speaking a foreign language can sometimes make me feel terrible,” then you’re probably familiar with some of these patterns.

You might start by downplaying your language skills upfront, then repeatedly apologize for mistakes. You may mumble to hide errors or hear a voice in your head urging you to just stay quiet. Further up the escalatory ladder, you might abruptly switch languages – say, to English – or even go completely blank. Eventually, you might throw in the towel, come up with an excuse, and walk away.

Experiencing these involuntary, self-defeating behaviors on a regular basis can be quite frustrating. For some, it’s merely an occasional annoyance; for others, these feelings are the very reason they give up learning a foreign language altogether.

Whatever your situation, you can do something about these patterns – they are not your destiny!

But before we explore possible ways out of this quagmire, we first need to understand better why and how exactly these patterns emerge.

School: Where Fear Is Learned

When we grow up, the goal in most school settings, especially in foreign language classes, is not authentic communication – it is accuracy. School is a practice environment where success is measured by how correctly you produce language. Teachers praise precision and often correct us sharply when we get things wrong. Every error carries social weight. Many students get laughed at by their classmates. Sadly, this is still tolerated as part of some dark pedagogy that believes shame and humiliation will turn us into higher-performing human beings.

I, for one, went through a startling metamorphosis between 5th and 8th grade. From an unburdened kid who enjoyed trying to express himself in foreign languages, I became a deeply insecure teenager who spoke English and French only with great reluctance.

To some extent, this can be seen as a normal part of adolescent development. At that age, we become more self-conscious, and it matters much more to us what others think of us. We begin to sharpen our social instincts and want to be accepted. Being seen as smart or cool becomes central – it's how we try to secure a higher place within the school’s social hierarchy.

At the same time, certain social traumas also play a significant part in how these patterns take hold.

In 7th grade, some of my classmates spent an exchange year in England or the United States. Then, in 8th grade, we had two exchange students from Australia in our class. Obviously, I couldn’t keep up with that level.

I have a vivid memory from English class that year: the entire room burst into laughter over the way I pronounced the word “doubt.”

“How dumb can one be?” said our teacher as the class kept giggling. “How often do you want to make that mistake?”

That day, I learned that you don’t need to know how to pronounce that word in order to develop some very severe ones about your own abilities.

Fear makes us shrink. And in school, mistakes become all too often associated with embarrassment, humiliation and a loss of status – with peers as well as with teachers.

To cope, we develop protective strategies: we self-censor, overcompensate, lash out, give up and stop caring. Or we strive for perfection and adopt harsh inner critics that keep us on constant alert. These defenses aren’t conscious choices — they emerge to shield us from rejection.

In psychology, these strategies are called schemas: deeply rooted patterns that we develop early in life to make sure our basic psychological needs are met – even under adverse conditions. They consist of:

Beliefs about the world: “Making mistakes is not acceptable.”

Beliefs about oneself: “I must not make mistakes.”

Beliefs about others: “If I make a mistake, others will think I’m stupid.”

Automated response patterns on an emotional, cognitive, and even physical level that are triggered in specific situations.

As you’re certainly aware, these belief and response patterns often continue to shape how we feel and act in a remarkably consistent way – even when they stand in the way of personal growth and human connection.

Maladaptive Schemas

Later in life — especially abroad — the rules of the foreign language game change. In the adult world, communication matters much more than accuracy. As a matter of fact, the only one that truly cares about being correct at this point – is probably you! (And maybe some ignorant jerks who don’t know what life is really about and correct you to improve their own shaky self-esteem.)

In the vast majority of real-life situations our relational value is linked to being able to participate and to connect. Others will appreciate us for expressing and showing ourselves – flawless syntax is just the icing on the cake.

Unfortunately, though, our self-esteem admin system has not yet been updated. In many situations, our linguistic inadequacies let our self-esteem drop when we try to speak – and our inner protectors get activated. As mentioned before, we start overthinking and speaking hesitantly. We apologize, mumble, or freeze up.

The tragic irony is that these once-useful schemas of self-esteem protection now became a massive liability. Instead of helping us connect and improve our social status, they isolate us further – and make us feel terrible about ourselves. We stand by helplessly and watch confused and frustrated, as our subconscious patterns work against us. In the end, our self-esteem drops because of the very measures that were originally supposed to maintain it.

Motivational discordance: a conflict of goals

In more abstract terms, this dilemma can be described as a serious conflict of goals – or, as the German psychologist Klaus Grawe, the founder of consistency theory, calls it: a motivational discordance.

On the one hand, there are two aligned approach goals: First, we want to connect with others. Second, we want to enhance our self-esteem and prove to ourselves that we are fully capable of managing the situation linguistically.

On the other hand, there are two interconnected avoidance goals. First, we want to avoid making mistakes to protect our self-esteem. But beyond that, we may also fear what our fear of making mistakes can do to us. We know that nothing good comes from the parts of us that take over in those moments. After all, we are not Dr. Bruce Banner, who transforms under fear into the mighty green creature known as the Hulk. Instead, as ordinary humans, we often just turn into stuttering, insecure kids who want to be somewhere else.

This anxiety about making mistakes – and thus triggering our protective coping mechanisms – consumes a great deal of energy and attention. As a result, these resources are unavailable for tackling positive challenges. At the same time, true satisfaction can never fully arise from achieving these avoidance goals, because they can never be completely eliminated – only temporarily kept at bay.

That’s why entering a communicative situation with strong avoidance goals in mind is a set-up for stress and disaster. If all we can think about is “Don’t make any mistakes” and “Don’t lose control.”, we will feel tense the entire time, behave inhibited, and be absorbed by self-focused thoughts.

And if – heaven forbid – we do make mistakes and are unfortunate enough to notice them, catastrophe strikes. Our house of cards collapses; we are overwhelmed by feelings of inadequacy on multiple levels and might eventually withdraw in defeat.

Inner conflicts need mediation

Once again, I want to challenge the misconception that self-esteem in the context of language learning is fixed, and that the topic is too complex for learners to address in a structured and effective way.

We’ve already outlined the issue in considerable detail. The next step is to frame it in a way that allows us to work with it using an established therapeutic method.

At its core, we’re dealing with a structural inner conflict. When multiple schemas are at odds with us – and with each other – we need to take action: we must engage with them, help them soften, and guide them toward reconciliation.

Throughout the history of psychology, there have been numerous attempts to address inner conflict by using different concepts and frameworks. For our purposes, however, one approach stands out as particularly promising: Internal Family Systems (IFS).

Solving the puzzle – by thinking in parts

IFS is a therapeutic model developed in the US starting in the 1980s which has evolved into a widely respected approach for addressing a broad spectrum of psychological and emotional challenges.

Its core is in the synthesis of two paradigms: the concept of a plural mind – the idea that the psyche is made up of distinct parts, as well as principles from systemic family therapy.

Personalizing our inner dynamics by imagining parts of ourselves as distinct inner persons offers a powerful path to self-understanding and healing. Each part has its own story, needs, and emotions—just like the real-life people we empathize with every day. By applying our natural relational skills inward, we can understand and resolve inner conflicts with greater self-compassion and clarity.

Essentially, IFS offers a non-pathologizing and intuitive framework that encourages people to approach their inner world with curiosity rather than judgment. Instead of labeling inner experiences as disorders or symptoms, it views every part – no matter how extreme or destructive it may seem – as having a protective role with a positive intention. More precisely, IFS organizes inner parts into three main categories:

Exiles – Wounded parts that carry the burdens of trauma, shame, or fear. They get usually buried deep within the psyche because their emotional intensity feels overwhelming – or even dangerous – to the system.

Managers – Protective parts that try to control our environment and emotions to prevent pain by keeping the Exiles from getting released.

Firefighters – Reactive parts that act impulsively and jump into action to soothe or distract from acute inner distress once exiles get triggered.

When we view the inner conflict described above through the lens of the IFS framework, the situation reveals itself as something that could be called the False Twin Trap.

The False Twin Trap

Starting to learn a foreign language like German as an adult often gives rise to a new part within us. This German You is only a few weeks or months old, yet we expect it to perform like a seasoned veteran of communication.

Whenever we start speaking German and this new part comes to the forefront of our consciousness, something strange happens. Depending on the situation, our inner protectors get alerted because they mistake it for the Wounded Child – the one who struggled with English or other foreign languages in school, and who is usually kept exiled deep within our system. Nevertheless, our managers and firefighters jump in and activate their well-oiled response patterns to shield us from feelings of rejection, embarrassment, or exclusion.

At the very beginning of this text, we noted that two situations are particularly stressful for language learners: speaking in front of a group and speaking with native speakers. Now we can better understand why. Both situations remind our protectors of ‘traumatic’ school settings. Speaking in front of a group triggers fears of social repercussions for making mistakes, while speaking with native speakers throws us back to the same time when we feared disapproval and/or punishment from a figure of authority. In that sense, native speakers act as stand-ins for our former teachers – they, too, always know when we are right or wrong.

However, it’s now also clear why these schemas in the form of our inner protectors are so counterproductive. Our German part doesn’t need protection from imagined social threats because making mistakes no longer carries real danger. On the contrary, the same behaviors that once served to protect us now have the opposite effect and lead to frustration, social disadvantages, and lower self-esteem in the long term.

Part II - Escaping the False Twin Trap

If you're looking for relief from this dilemma, there are two options: an immediate, temporary fix and a sustainable long-term solution.

The first one is rather easy: put yourself into a social situation where you’re required to speak German – and get drunk.

As a teacher and coach, I don’t usually recommend combining drinking and learning. But – and I say this with some seriousness – if you suffer from xenoglossophobia (the fear of speaking foreign languages), and you’ve never experienced what it feels like to speak German without anxiety, this experiment might be worth considering.

Alcohol suppresses your overly cautious and critical managers as well as your overreactive firefighters. It lowers the volume and impact of these voices and will therefore reduce inhibition and self-monitoring.

As a result, you will speak more freely, more fluently and without fear. Yes, the quality of your speech might decrease – but you will neither notice nor care because your protectors are offline.

It might be surprisingly eye-opening to get a concrete sense of what the ideal state of mind for speaking a foreign language actually feels like – unless, of course, you get too drunk to remember.

Also, be aware of the side effects. Apart from dizziness and a headache, your temporary freedom could come at a cost. Once the alcohol wears off, your protectors might return with a vengeance:

Your Managers may haunt you with more shame and criticism: “You embarrassed yourself!”

Your Firefighters may whisper: “That felt good. Let’s do it again. And again. This might be the solution to our problem!”

Don’t listen to them – because it is not!

Escaping the False Twin Trap for good

If you are serious about finding peace with your protectors and improving your self-esteem long-term, you’ll need a certain degree of commitment and willingness to do inner work. This is a path of self-exploration, self-acceptance, and, ultimately, healing – and it’s without a doubt worth your time and effort.

You can absolutely embark on this journey on your own – I’ll provide all the materials you’ll need below.

However, I strongly recommend doing this work, at least in parts, with others. Speaking things out loud has a much greater impact than simply thinking them. We also tend to think more clearly and deeply when we articulate our thoughts – especially when we’re being guided.

You could work with a friend or another language learner as a facilitator, using the same materials. Or you might consider joining one of the workshops I offer regularly.

That said, the best results come undoubtedly from working with a trained therapist, such as Fraeya Whiffin. She’s a British IFS practitioner based in Berlin who has a deep understanding of the challenges involved in learning German.

The journey involves at least five steps – some of which you may need to revisit multiple times.

Get in Touch with your „Self“

Hallo Du! – Meet your „German You“

Meet the Team: Your Foreign Language Protectors

Interview with a well-known Stranger: Befriend and Validate a Protector

Healing the Core: Unburden the Exile

It’s important to understand that you don’t need to complete all the steps to start feeling the effects. Each exercise will bring you closer to yourself – and to the inner peace you seek to speak German with more confidence. That said, I’d still like to give you a sense of what a complete journey to more self-esteem would look like.

First Step: Get in touch with your „Self“

The first important thing to experience is that you are more than the sum of your parts. For there is something in your mind that is not a part. A soul, so to speak, the core of who you are beneath your fears, defenses, and learned patterns. In IFS this is called The Self.

Accessing the Self, or being self-led, is a state of complete equanimity. That means not only being utterly undisturbed by the experience of emotions, but being able to face the other parts with calm, courage, curiosity, and compassion.

We can access the Self through the conscious process of disidentification – or unblending – from our inner parts. Thereby creating an inner space where all voices can be heard without one taking control or taking over altogether.

It’s a place that is rather difficult to describe with words. That is why I want to invite you to a short meditation, where I guide you through the process of unblending from your parts. As a matter of fact, this state of mind is generally a sought-after result in mediation, and you’ll probably find it rather pleasant.

That, however, is not the reason why discovering your Self is worthwhile. To even begin the path out of the False Twin Trap it is important to establish a safe zone and a high ground from which to overlook the inner landscape of your mind. A place, at last, from which you can safely meet yourself and all the parts you consist of – especially the hidden and unpopular ones!

So, sit comfortably. Close your eyes, and take a few deep breaths…

Click here for the script of the guided mediation.

Second Step: Hallo Du! – Meet your German You

We often place unrealistic expectations on the very young part of us that speaks German. We put it under a lot of pressure to perform. But that’s likely not the best way to support it, especially if we want it to be well and grow stronger over time.

In the following exercise, we will therefore be curious and connect to that new part of us. We’ll leave judgment behind, and give it the patience and care that every part of us deserves. Prepare for some surprising insights, and click here for the script! (Or here for the script in German - in case your German You wants to express itself in German…)

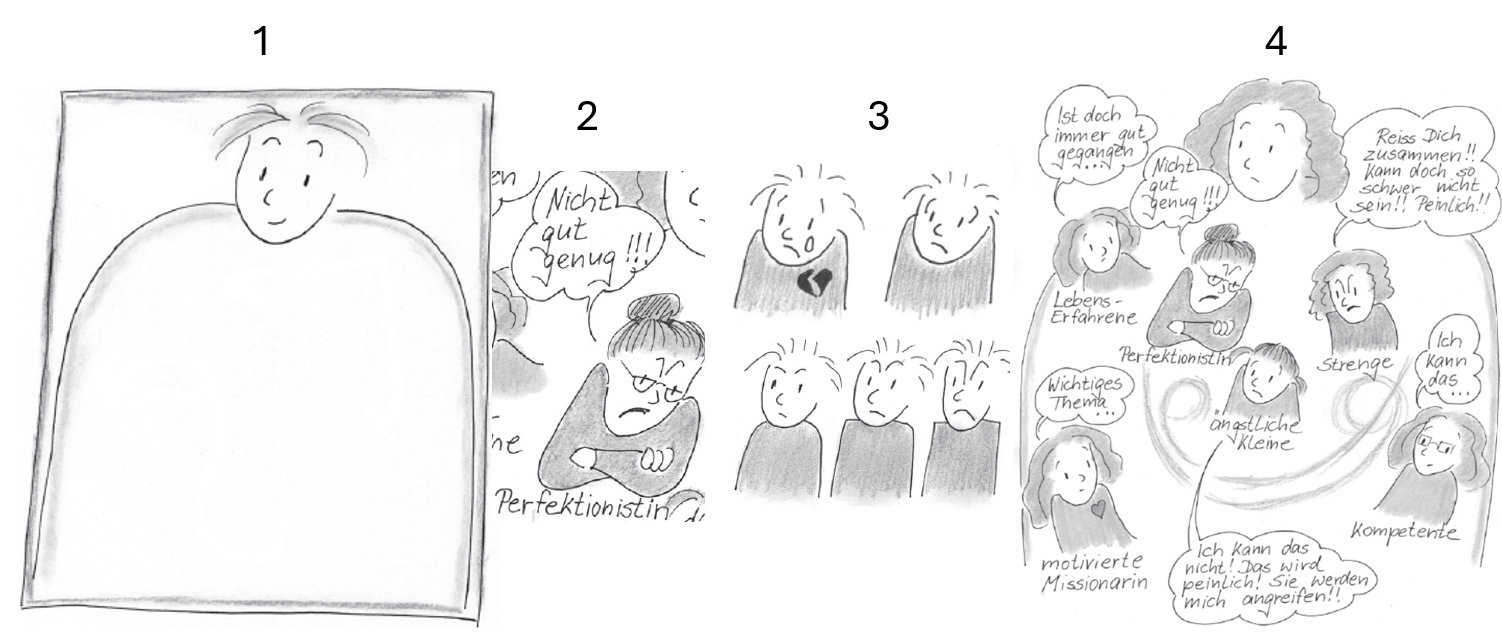

Third Step: Meet the Team – Your Foreign Language Protectors

This exercise is designed to help you take stock of all the protectors that might show themselves when you speak German. Surely, you identified and named some during the previous interview with your German You.

Each person has a unique set of protectors. But there are some managers and firefighters that tend to be quite common among foreign language learners.

Common Managers

The Perfectionist – demands flawless grammar before speaking.

The Critic – constantly points out mistakes or flaws.

The Comparer – compares progress to others obsessively.

The Overthinker – overanalyzes every sentence or response.

The Avoider – prevents risks like talking to natives or going to places where ones has to speak the foreign language.

The Researcher – wants to know everything before trying.

The Monitor – tracks and evaluates every performance moment.

The Judge – harshly evaluates your language performance, turning every small mistake into a verdict of inadequacy

Common Firefighters

The Quitter – says “Just stop this now.”

The Isolationist – tells you to go back home.

The Inner Screamer – is intensely frustrated with the whole process.

The Language Switcher – automatically reverts to your native language or English in moments of stress.

The Apologizer – says “sorry” constantly, for grammar, accent, or even speaking at all.

The Mumbler – makes you speak faster, unclearly and in a lower voice to hide mistakes.

The Blanker - suddenly wipes your mind clean—you forget even simple words.

The Freezer – shuts everything down when the pressure to speak becomes too overwhelming.

The Justifier – comes up with elaborate reasons why you don’t really need to speak or learn the language.

The Clown – makes fun of the language and the country.

The Hater – lashes out at the language and the country to deflect and shift the emotional intensity outward.

Now, I invite you to grab the biggest sheet of paper you can find and get ready to do some drawing. Don’t worry, you don’t need to be a Picasso for this. In fact, the less artistic your drawing skills, the better! This isn’t about creating a timeless masterpiece, but about visualizing and exploring your inner schemas.

Start with the empty frame on the left. Make sure you leave enough room for your full inner team of protectors.

Draw a figure for each part. Give each one a name and add a speech bubble with a typical phrase that captures its role or attitude.

Show how these parts feel when you speak. Use features like eyebrows, shoulders, or symbols to express emotion. You can also use the length and curve of the mouth to show the intensity of each feeling.

Finally, show how these parts relate to one another. Draw connections, tensions, or alliances between them—whatever feels true to your inner system

Ideally, once you're finished, take some time to explain your drawing to someone else. Speaking it out loud not only deepens your understanding, but also helps you connect more consciously with the parts you've visualized.

Ideally, once you're finished, take some time to explain your drawing to someone else. Speaking it out loud not only deepens your understanding, but also helps you connect more consciously with the parts you've visualized.

Fourth Step: Interview with a well-known Stranger – Befriend a Protector

This fourth exercise is a little moe advanced. You’ll be stepping into the known-unknown and making direct contact with one of your manager or firefighter parts.

Imagine you're attending an inner team meeting. Look at the drawing of all your foreign language parts. Which of your protectors feels closest to you? Who is the loudest, or pushes themselves into the spotlight? Who seems to need your attention or support the most? Which one sparks your curiosity? And if there's one that intimidates or scares you a little – that’s exactly the part you might want to start with!

The goal of this exercise is to begin a conversation with your most dominant protectors. You’ll get to befriend and validate them, understand their good intentions and appreciate their history and the burdens they carry. You’ll also explore who or what they’re protecting, gain insight into their fears, and find out what they would need to let go of their role.

Click here for the script for you Interview with a Well-Known Stranger.

Fifth Step: Healing the Core – Unburden the Exile(s)

This final exercise is probably the most challenging and can be difficult to practice without a trained facilitator. Nevertheless, it’s very useful for gaining insight into what it takes to access and heal the very core of your inner conflict: your exiles.

In painful or traumatic childhood experiences, parts of us can become emotionally “frozen.” These exiles are often loathed or feared by other parts, which then work hard to keep them locked away. If we want our protectors to change their behavior, we must convince them that there is nothing left to protect us from.

In IFS, this process is called Unburdening and consists of the following seven steps.

Get permission from protectors: Before accessing an exile, you must ensure protector parts feel safe and agree to let you interact with the exile. They might fear that connecting with the exile will overwhelm the system.

Witness the exile's experience: Once protectors step back, you connect with the exile in a compassionate, calm state. You allow it to tell or show you its story – what happened and how it felt.

Validate: The Self offers compassion, empathy, and understanding. The goal is not to fix or change the exile right away but to genuinely witness it without judgment.

Retrieve: If the exile is "stuck" in a past time or place, you help it understand that it’s not alone anymore. You mentally or imaginatively "retrieve" it from that memory, letting it know it's safe now.

Unburden: The exile lets go of the extreme emotions, beliefs, or energies it has carried—like shame, fear, or worthlessness. This can involve a symbolic ritual: dropping a heavy bag, or burning a belief.

Invite in new qualities: After unburdening, the exile can take in new qualities like confidence, playfulness, or calm.

Integration: The Self invites protectors to notice that the exile has unburdened and feels healed, then asks if they are ready to find new jobs and helps with this if they need help.

Click here for the script for Unburdening an Exile.

I sincerely hope these exercises bring you insight and a sense of relief. Calming your protectors and finding inner peace when speaking and learning a foreign language can be a longer journey.

Despite what some self-help gurus claim, we can’t simply decide to have more self-esteem. It must be earned. It takes real work.

If this kind of inner work has sparked your curiosity and you’d like a bit of support on your path out of the False Twin Trap, don’t hesitate to get in touch.

In the long run, it pays to be curious and courageous – especially when it comes to yourself. And who knows, you might discover a world and a method that not only brings you inner peace in language learning but could potentially transform your entire life.

What do you have to lose?

Recommended Reading

If you’d like to explore the topics covered in this text further, here is a brief list of recommended books, along with links where you can access or purchase them.

Branden, Nathaniel (1995). The Six Pillars of Self-Esteem.

Leary, Mark (2012). Sociometer theory and the pursuit of relational value: Getting to the root of self‑esteem. (PDF)

Schwartz, Richard / Sweezy, Martha (2019). Internal Family Systems Therapy.

Schwartz, Richard (2023). Introduction to the Internal Family Systems Model.

Schwartz, Richard (2024). The Internal Family Systems Workbook: A Guide to Discover Your Self and Heal Your Parts.